Question 2: Are resources scarce?

If scarcity is a real economic problem, why then most business founders find selling products and services the hardest thing to do? Is scarcity real?

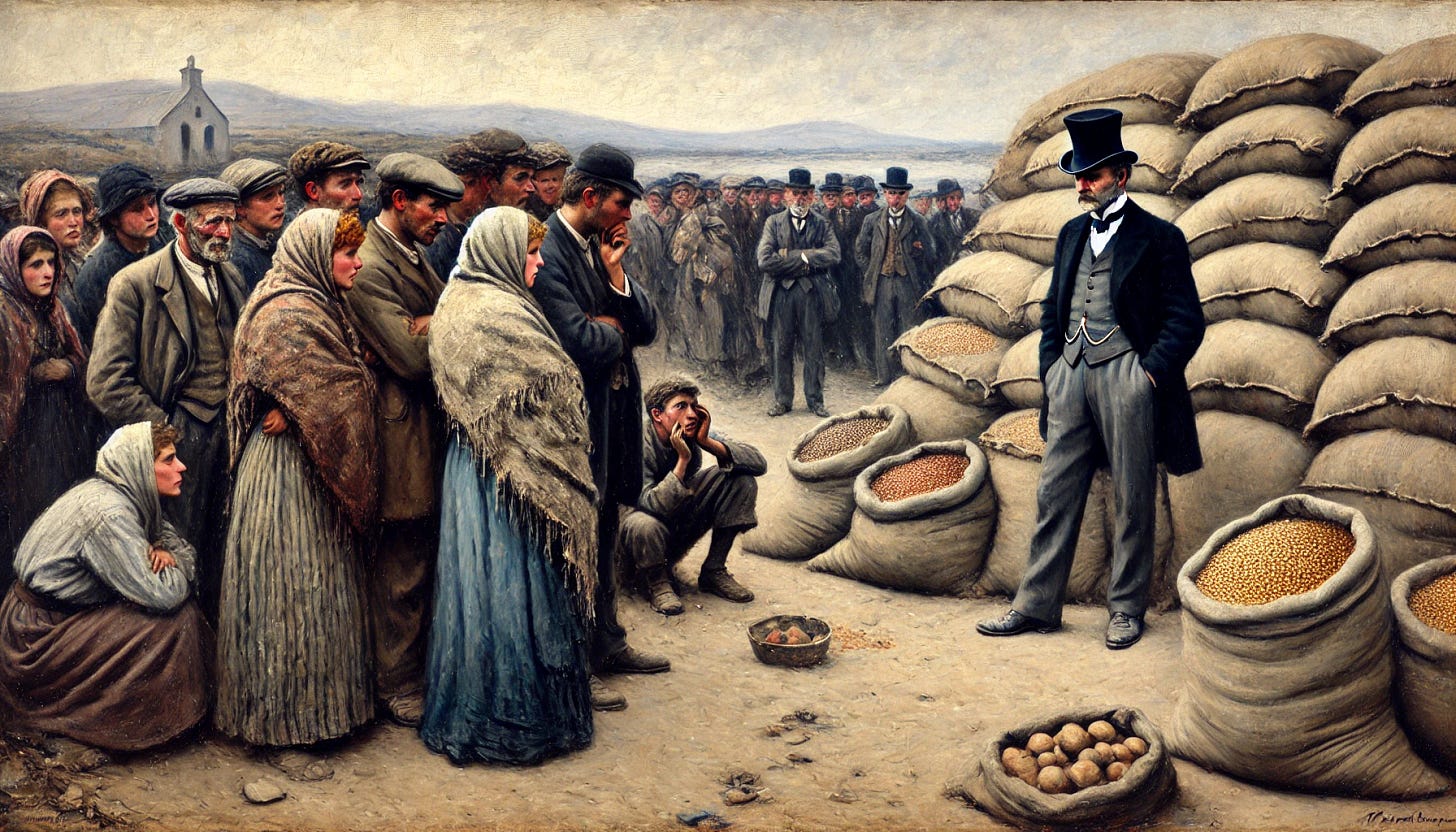

The ultimate scarcity: the Great Famine

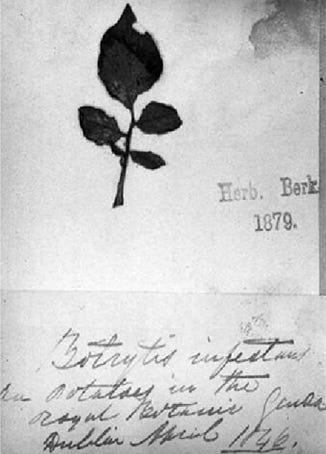

David Moore, the director of the Royal Dublin Society’s botanic garden at Glasnevin, made his first troubling discovery on the 20th of August 1845. Moore had the first recorded observation of what would later become known as the Blight – the disease that decimated potato crops in Ireland in 1840s, causing mass death and emigration between 1845 and 1849.

“Gorta Mór” or the Great Famine took an estimated one million lives, two million people emigrated from Ireland in the subsequent decade, bringing the population that was growing steadily until then down from 8.2 million to about 6 million in 1855. By 1901 Ireland’s population fell to 4.4 million due to the trauma, reduced fertility rates and economic hardship in the wake of the famine. Ireland’s population never properly recovered from this tragic event.

Frightening as these numbers are, they fail to convey the true degree of the tragedy. One commander from the British navy recalls his observations in Cork county on 15 February 1847:

“18,000 inhabited the parish, three quarters of that population were skeletons with swelling of the limbs and diarrhea universal… cabin contained an old woman and her daughter, whose husband had deserted her with three little children. The grandmother had already died. The fourth cabin also contained a corpse which had been lying there for 4 days – no one could be found with sufficient strength to take it away”.

Any famine emphasises the fundamental economic principle of resource scarcity; Mother Nature herself dictates the limits to available resources. But not without a lot of help from mere mortals, as we shall see.

What caused the Famine?

The potato was introduced in Ireland in 1580s and quickly grew to become a dominant crop due to its tolerance of the wet and cold climate and good nutritional values. By 1840s Irish potato crops reached 15 million tons annually, of which 7 million was consumed by humans, with the rest used as animal feed, seed and export. In the early 1800s, an adult male laborer in Ireland consumed 6.4 kg of potatoes a day. The poorer part of the population depended entirely on potatoes and buttermilk for their dietary needs.

It is in this backdrop that David Moore draws a troubling conclusion based on his observation of potatoes in the botanical gardens: the mystery disease impacting potatoes in parts of Europe and now in Ireland is likely to be a fungus. DNA analysis carried out in 2007 using the fragments of the pathogen from the sample supplied by David Moore confirmed that the source of this Phytophthora Infestans fungus was the region of Andes in South America.

The impact on the Irish potato crop was devastating: crops fell from the pre-blight 15 million tons to 1.2 million in 1846, 1.7 million in 1847 and 0.5 million in 1848. This was nature’s ultimate statement of need, a frightening exhibit that the law of scarcity in Economics is as immutable as the law of gravity in Physics.

Scarcity or choice?

A closer inspection of the circumstances of the Great Famine, however, paint a completely different picture. Ireland joined a union with Britain in 1801. So the question of whether there was scarcity must be considered in the context of Britain – the greatest economic power of that time. Could Britain afford to remedy the situation and avoid the devastating famine in Ireland?

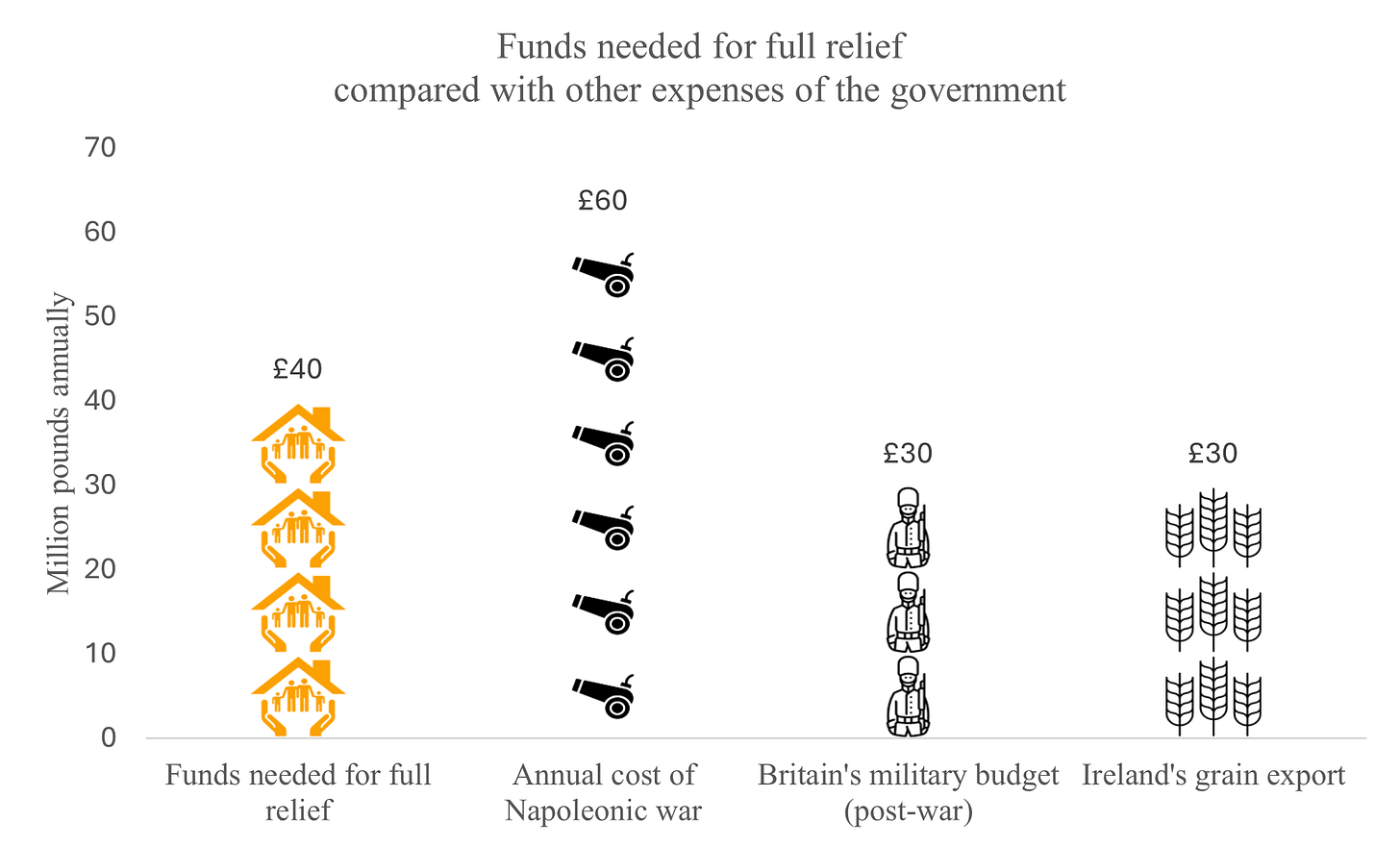

Based on the nutritional values and the number of people, Ireland needed 2.5 million tons of grain a year to substitute the missing potato crop. Wheat was an expensive option, so the British government imported and distributed the considerably cheaper maize (Indian corn) from the US, albeit in very small volumes of 100 thousand tons, which was incidentally sufficient to avoid deaths in 1845. The cost of imports and distribution of 2.5 million tons of maize, even accounting for rising prices would be in the range of £25-30 million.

This is no small change, of course, considering the estimates of overall GDP levels at £400 to £500 million. But the question remains – could the government manage to finance at least a partial (if not full) relief? Was there a precedent of financing of major government spending at that time? Well, how about the Napoleonic war? British government spent an annual average of £60 million during the Napoleonic war, financed with excise and customs duties, income tax and long-term borrowing.

That still does not fully negate the fact of scarcity. Surely Ireland by itself, without help from the British government could not sort out the issue? But despite the famine, Ireland continued to export grain (wheat, barley) to England and elsewhere throughout 1840s. Granted that the exported grain volume was low, but the exports were of higher value grain. In value terms, Ireland’s own grain export could have been in the range of £20-40 million!

What stopped Ireland from banning exports or using the export proceeds fully to meet the needs of the population? The quick answer is a combination of:

land ownership and rent structure (export crop owned by land owners)

central government’s full belief in self-dependence and free markets

A good indication of the prevailing moods in the British government could be expressed in this passage borrowed from a historian and author Christine Kinealy’s book on Irish famine. The passage is an extract from a letter of Charles Trevelyan, who as assistant secretary to the Treasury at the time managed the Treasury’s purse when it came to the relief efforts:

“That indirect permanent advantages will accrue to Ireland from the scarcity, and the measures taken for its relief, I entertain no doubt. . . . Besides, the greatest improvement of all which could take place in Ireland would be to teach the people to depend upon themselves for developing the resources of the country . . .” (Trevelyan to Routh, 3 February 1846, p. 77).

Reluctantly glossing over the dubious morals of the statement, we are left again with the all-powerful principle of scarcity invoked here. But the real driver behind the refusal to do more to help the population is the fundamental belief in the sanctity of the unincumbered (or free) markets.

Ah, but were the markets really free? Did all participants have a free choice? What choice did Irish farmers have at the time?

Monoculture or death

A key natural reason for the famine was the concentration of all agriculture on a single crop. However, Irish farmers had no choice in this matter. Land was owned by aristocracy and let to middlemen, who then sublet increasingly smaller plots to a larger number of farmers. The level of rent was driven by the crop with the highest yield and the least required effort, as many farmers had to work on the owner’s land in lieu of rent payment. Farmers did not have a choice of diversifying the crop to limit risks, as that would make the rent payment impossible.

Ultimately, this version of the free market diverted all the upside from the high risk of single crop to the government and the aristocracy in the form of taxes and rent, and offloaded the risk to farmers who had no say in this “contract” and as Charles Trevelyan put it, had to be taught to depend on themselves.

As it happens, the Irish Famine is only one engineered scarcity event in a string of events, including the Great Chinese famine, the Holodomor, the Bengal famine, the Ethiopian Famine – all cases that had nothing to do with true natural scarcity in the spirit in which Economics textbooks discuss scarcity.

Where does scarcity come from?

The real scarcity is an outcome of the adopted or imposed rules of the game - ideology and regulation. Let’s look at another example to better understand the issue of scarcity.

Drew Curtiss set up Fark.com as a news aggregator in 1990s. The website itself is not remarkable or unusual, but what happened to Drew is very telling. The idea was to collect curious news items on a website instead of exchanging emails with friends (remember, this is pre-social media). But Drew’s firm was sued for patent infringement in a patent troll case in the US. The claim was that Drew website infringed on the patent, which describes “Writing three key messages … two to three statements that support the HEADLINE and entice the reader;…”, in other words, this was a patent of something that everyone would consider a part of writing a message.

Such a patent grants the ownership claim for simply writing a message, and while probably unenforceable in the court, can be used by the holder of the patent to extort hundreds of thousands of dollars from victims, since defending against the lawsuit would cost over a million dollars.

Austin Meyer an aerospace engineer, computer programmer and the man behind Xplane flight simulator software was himself sued by a patent troll and made a documentary covering many similar cases of patent trolling. His main message was that none of these suing firms actually created products, services or used the patents themselves in any way. But patent trolling is not a bug in the whole intellectual property field, it is a feature!

A simple abundant and unrestricted resource, such as writing a message, can become scarce and cost money, if we impose an ownership rule. The reader might argue that patent trolling is more of an exception rather than a rule, that patents are far more clearly defined in more serious intellectual property cases. But if merely writing a message appears to be a no-brainer and unworthy of a patent to regular people, most experts would find the contents of most patents in their specialist fields a no-brainer or common knowledge. Intellectual property laws are designed to create and exploit scarcity where no such thing naturally exists.

How about scarcity in the tangible world?

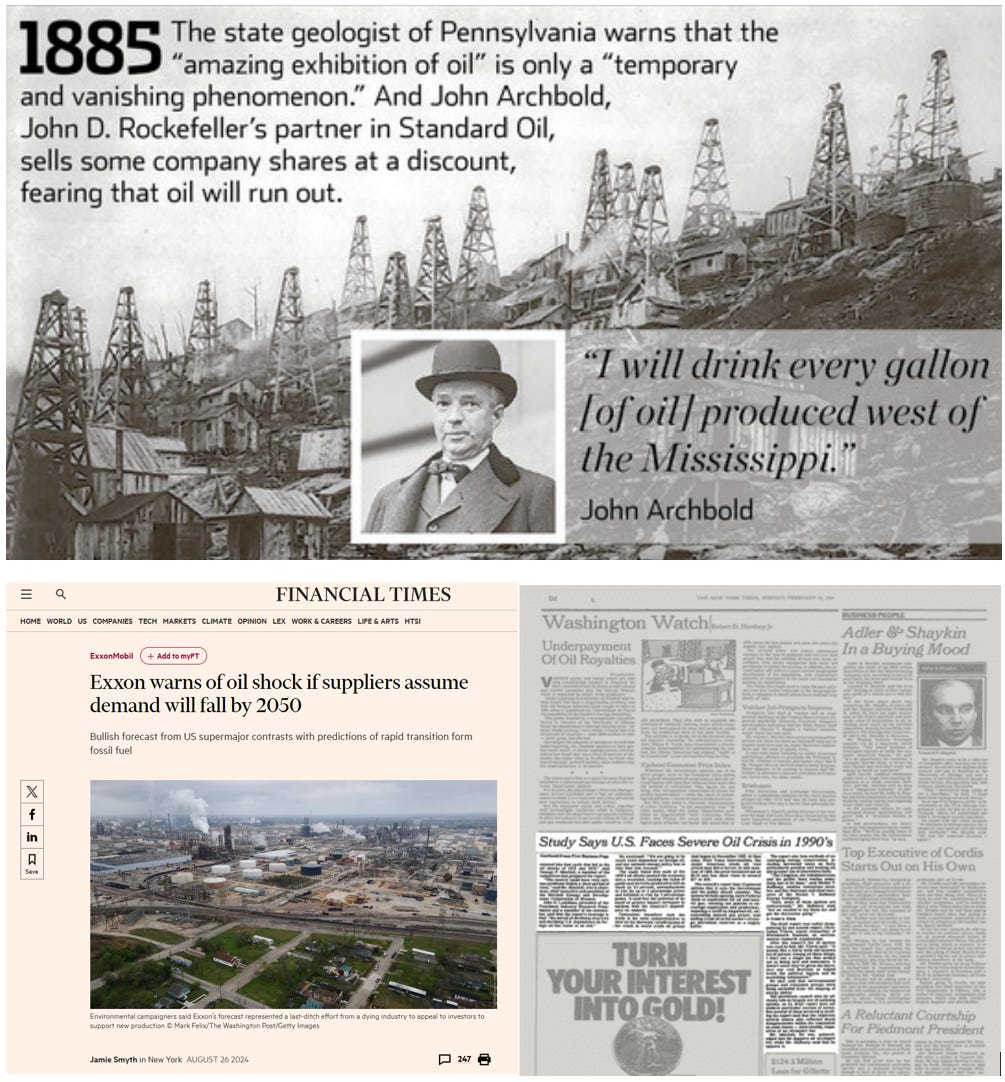

Surely there must be real constraints in the natural world, particularly when it comes to the natural resources, for instance, the resource for which dozens of wars have been fought - oil? The world’s obsession with the peak oil theory – the idea that we will run out of oil, started almost as early as the commercialization of oil.

Nothing like an occasional manufactured panic of the world running out of a resource to prop up prices or induce more preferential regulation, which explains occasional press articles about collapse of oil supplies. This is a very common tactic not only in the oil but virtually in any industry that can place remotely credible claims of scarcity. A war in Russia? The world will run out of neon, sunflower oil, gas and electricity. Covid? The world will run out of toilet paper, medical equipment, test kits and everything else.

Yet it is remarkable how the world managed to get by without a hitch even with nearly 25% of the population in the industrially developed countries out of work, or pretending to work from home.

The only reason we did not experience mass starvations similar to the Great Famine is that the modern governments are (for the time being!) more democratically accountable and were forced to act to change the rules of the game. There was no real impactful scarcity of resources.

Despite years of sanctions and the devastating war in Ukraine that consumes an estimated $ 500 million per day(!) of Russian resources, an average person in Moscow still consumes the same products bought in the same supermarkets and an average person in Tyva still can’t afford the minimum required to sustain life. Ownership rights, government control and imposition of the rules of the game are the core drivers of scarcity during the Covid, in Russia and in the oil markets. The worst oil crisis that the West ever endured had only a political cause and nothing to do with physical scarcity.

Of course, there is clearly a physical limit to the quantity of oil and other resources on our planet. This is a Physical argument that has always been used to create the basis of the scarcity myth. But what if any physical limit of resources is not binding in any practical way?

Our ability to adapt is limited only by time and our evolving preferences. In the aftermath of the oil embargo in 1973 the US oil consumption fell by nearly 20% simply by redesigning the vehicles and buildings. The society adjusted its preferences and in a few years required 20% less of the resource. This raises the question of preferences or desires and their relationship to scarcity.

Unlimited desires and scarcity

One unassailable argument in favour of the scarcity fib is people’s unlimited desires. An Economics 101 student accepts at face value the “fact” that people’s desires are unlimited. The conclusion of scarcity is natural, since there is no physical quantity of resources that can meet unlimited desires.

What is often overlooked is that the student accepts this premise only by observing the society in its present hyperconsumerist and commercialised state, where every human feeling from love (Valentine’s day) to benevolence (Christmas) is commercially repurposed to create desire for things.

A very important question that fascinated clever minds for centuries has been sanitised from the body of scientific knowledge of Economics. Should we accept that human desires are unlimited?

Humans are carbon-based life form that naturally require about 3 kWh (2500 kcal) energy per day and operating temperatures of between 18 °C and 25 °C. We have a body with certain dimensional limits. The need for food (energy) and shelter (temperature) that are necessary for our existence, have a natural limit expressed by the numbers above. In fact, anything significantly more than these numbers will be absolutely harmful to us. So why insist on this idea of unlimited desires if the clear limits are in our nature?

There was time when the clear limit of our natural biological desires was accepted and understood across the spectrum of conflicting schools of thought. Plato in his magnificently totalitarian and reactionary “Republic” does distinguish between the necessary and unnecessary desires:

“Are not necessary pleasures those of which we cannot get rid…, because we are framed by nature to desire both what is beneficial and what is necessary. … And the desires of which a man may get rid, …of which the presence, moreover, does no good…shall we not be right in saying that all these are unnecessary? Will not the desire of eating …simple food …be of the necessary class? And the desire which goes beyond this, of more delicate food, or other luxuries, which might generally be got rid of…may be rightly called unnecessary?”

Later Greek philosophical schools of stoicism and epicureanism disagree about most things, but find a strong agreement on the distinction between natural and necessary and unnatural or unnecessary desires. Epicurus goes even further stating that:

“The wealth demanded by nature is both limited and easily procured; that demanded by idle imaginings stretches on to infinity.”

This last simple sentence paraphrased in the modern language means that natural human desires are limited and there is no real scarcity when it comes to satisfying those desires.

Can the planet sustain us?

Epicurus’ statement was probably true when the world population was at most 100-200 million. How reasonable is it to assume that our planet could sustain the rapidly rising population currently at around 8 billion?

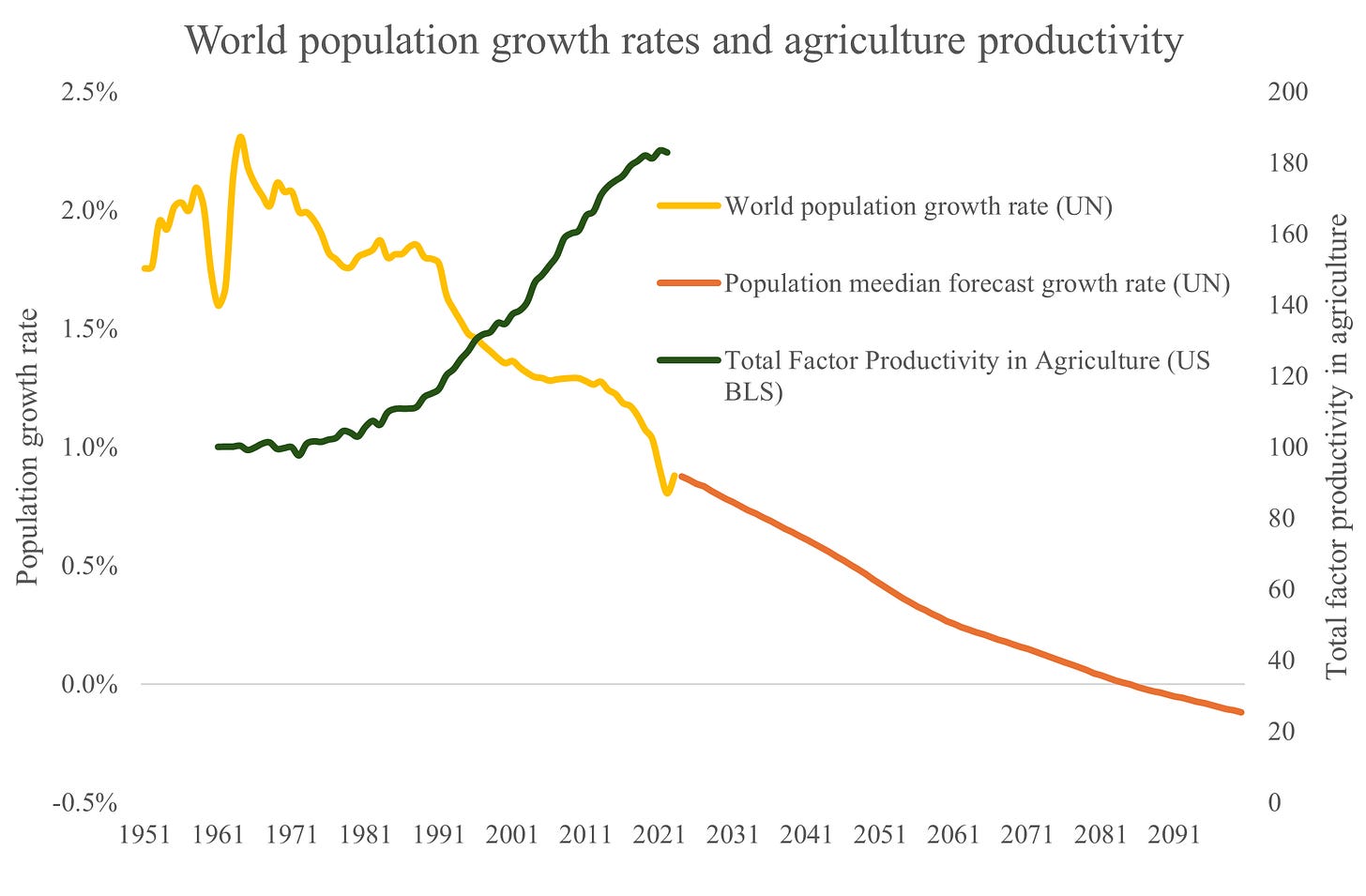

The degree to which our collective ability to produce food has improved is often underestimated. Today the world produces sufficient amount of food to feed by different estimates approximately 9 to 10 billion people, albeit a large part of it is wasted and lost in distribution or simply denied to few hundred million people who starve.

While the rate of population growth is falling, the rate at which we get better at producing food (total factor productivity in agriculture) keeps increasing. This is a very divergent picture from the one Thomas Malthus painted in the nineteenth century (and inspired, among others, the British government’s atrocious response to the Irish famine).

Even considering the environmental sustainability constraints (including the shortage of ground water, overuse of chemicals etc.) the world is perfectly capable of satisfying the natural desires of 10 billion people for food and shelter with today’s technology.

However, it is important to understand that most climate scenarios carried out by financial institutions and corporations are faulty simply because they disregard the likelihood of emergence of new “needs” that require greater energy and emissions such as same-day delivery of online purchases or more lanes on highways for peak hour traffic.

The question is whether we choose to abandon the scarcity myth and redesign our economic performance indicators to measure what matters: how well the society satisfies the necessary and natural requirements of the world’s population for food and shelter? Isn’t everything else an optional extra that can be thought about once this primary goal is accomplished?

Or we insist on prioritizing technologies such as Bitcoin; it consumes160 TWh (Poland’s annual energy consumption) for solving abstract mathematical problems for no particular reason enabling payments for organized crime, terrorism and drug trafficking, with a CO2 footprint of 1600km car journey per single transaction?

What is the biggest selling point of Bitcoin? An artificially and intentionally manufactured scarcity designed to mathematical perfection!

-WH