Question 3: Is Consumption a Valid Measure of the Economic Performance?

Using alternative measures, the US economy failed to improve since 1980 and lags considerably behind that of Germany and France.

“Look at Mrs. Jones!”

The 1881-82 issue of The Banker’s Magazine and Statistical Register contained a brief article titled “Remarkable banking” – one of hundreds of truly forgettable articles on topics ranging from taxes in Turkey to losses in the French panic. Apparently, the shares of Chemical National Bank had reached $1780 – “the highest quotation of any banking house in the world”. The founder of the bank – John Mason, having failed in the chemical business, was left with a banking licence (“privilege”) and went on to build a successful banking business, with resulting:

“…dividends of 25% per quarter and the present astonishing quotations. John Mason was the dry goods colossus of his day and left a large fortune.”

John Mason’s fortune went to his children and their spouses, among them – Isaac Jones. The Joneses were astronomically rich by the standards of the time, and began spending the fortune on building country villas in the Hudson Valley. As each villa was grander than the previous one, other wealthy families felt obliged to compete with that opulence, but “keeping up with the Joneses” was difficult. This term was later popularized by Arthur Momand in his eponymous comic strip in 1913.

Today, as ten thousand years before the Joneses ever set foot in New York, we are hard-wired to mimic each other as an effective way to connect and cooperate. Successful cooperation helped us eliminate natural predators in our environment and adapt to the elements.

But just like our bodies are wired to have insatiable appetite for fat and sweet food, our mimicking behaviour left unchecked can be a serious health hazard.

We may have inadvertently built our whole economic measurement and policy infrastructures on the back of our desire to mimic, and there is no physician that can put us collectively on the “scale” and warn us about the negative effects.

The hedonic treadmill

Moving into a new neighbourhood and taking a new, higher paying job can be a fantastic opportunity for a better life, but it comes with implicit requirements of dress code, brands, cars, hedge trimming equipment, lawn mowers, solar panels on the roof – anything that signals the fact that we belong.

We begin to enjoy the new neighbourhood, and even the new hedge. For about a month. But then unnoticeably the novelty wears off and with it – the sense of elation and achievement. We hit the hedonic treadmill.

Hedonic treadmill refers to our inability to feel happiness or elation for an extended period of time. Research has shown that people have set-points of “happiness” defined by individual genetic disposition to feel happy. Any improvements in the financial situation, new purchases or career advancement increases the degree of experienced happiness only for a short period of time, after which we revert back to the set-point.

Early empirical studies of hedonic treadmill in the 1960s and 70s showed that the happiness “set-point” is impossible to change permanently. The way to keep the flow of positive emotions is by buying more. Each purchase causes a new temporary high, but the next purchase has to be even bigger and more impactful.

The toxic cocktail

Each trait taken separately has its evolutionary purpose: mimicking helps us cooperate, while the hedonic treadmill helps us limit energy consumption. In the modern economic context, however, the two traits conspire to play havoc with our lives. To illustrate this, consider the story of Grace, retold from one of thousands of online articles on the subject:

"…what you’re doing is feeding the feeling or the emotion and there is that feelgood, short-term fix in that moment until you come away from it and reality hits home and the guilt sets in when you realise that maybe you’ve overspent, or spent money you shouldn’t have… When asked how much debt she currently has? …£25,000...That figure is spread across bank loans, credit cards …and another credit card she uses as her 'spending' card. Yet she does worry about not having an 'emergency fund’ ... Grace currently has £1,000 in savings."

Clearly, Grace is all too well acquainted with the short-term high of the hedonic treadmill, while the urge to spend and the ideas come from her environment: “…Because I have been working in financial services for 10 years, I am well versed in how I should be doing these things. In my position at work, I manage millions”.

Before the reader jumps to the conclusion that one woman with shopping addiction does not make a trend, a recent study carried out by a group of researchers from National Formosa University, Taiwan and Berkley identify a strong tendency of shopping addiction to relief stress among a sample of 380 graduates, of whom 68% male and 32% female.

Remember our personal set-points of happiness? Taken individually, our set-points would just keep us wanting things at a steady pace. But if Grace’s set-point depends on her colleagues’ purchases of bags, shoes and holidays, then everyone else’s purchase puts Grace below her set-point of happiness. This means everyone else’s purchases make Grace less happy than her natural state. She has no choice but to buy.

In a simulation model developed by Alastair Langley from Bristol University, this toxic cocktail results in higher income (marginal cost of consumption) reducing welfare!

But what is the problem with Grace, her colleagues and all of the students at university of Taiwan consuming all they want and feeling happy? After all, most people unlike Grace are perfectly capable of managing their impulses and keeping their consumption levels within their means. Unfortunately, as we shall see, the problem of the toxic cocktail and our inability to reflect it in the economic policy has negatively affected whole societies in a measurable way.

Textbook Economics take on human nature

Economic thought has progressed considerably when it comes to human behaviour. Fields like behavioural, institutional and evolutionary Economics have relaxed many unrealistic assumptions about human behaviour. But one thing has not changed: the way we measure the ultimate goal – welfare or utility achieved through consumption.

All warring economic schools, to the extent they define any end goal, focus on the sum of utility gained from consumption.

Incidentally, the sum of all personal consumption, albeit in money terms, is a key ingredient of the main gauge of economic prosperity currently used by policy makers worldwide – Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As far as GDP is concerned, the more Grace, her loved ones, Taiwan university students and everyone else consumes, the better our economy performs.

The hamster wheel ignored by Economics

Grace’s total utility would be the sum of utility she receives from purchases today and every other day in her life, and the sum of all the utility her fiancé – Oliver receives through his life, because Grace cares about Oliver. If the society consisted of only Grace, her fiancé, her colleague Justin and his wife Amelia, the total utility of the society would be a simple sum of all utilities:

Total social benefit = Grace + Oliver + Justin + Amelia

But our toxic cocktail implies something entirely different. Remember, that if Justin (Grace’s colleague) buys a new toy, let’s say (pun intended) a new treadmill and posts the picture on Facebook, it makes Grace less happy compared to her set-point!

That means, when Justin or Amelia buy the treadmill, any gain they have may be offset by the loss in happiness that Grace and Oliver experience from their set-point. So the additional purchase of Justin and Amelia may not add anything to the total social benefit – a form of a society-wide hedonic treadmill.

Total social benefit = - Grace - Oliver + Justin + Amelia

(to answer any criticism of the mathematics involved: I understand the equation must look at the first difference, but this is just a simple stylised representation to make a point)

All the while, the GDP would reflect the new purchase and show a clear improvement in social benefit. Worst of all, the society cannot improve the total welfare by additional consumption – it’s stuck at the set-point. But things are actually much worse!

Lost TIME

Early research on hedonic treadmill was revisited and expanded, and recent broader studies suggest that:

some new spending on physical goods does succeed in moving the happiness set-point permanently, particularly when it comes to owning basic necessities such as shelter (owning a home) and food

spending on experiences does create more sustainable happiness

more strikingly, life goals of purchases appear to matter: goals such as “commitment to family, friends and social and political involvement” successfully move the set-point upward, while zero-sum goals, such as commitment to career success, material gains, appear to be detrimental the happiness set-point.

But revisiting our Economic utility equation armed with this knowledge raises an even more troubling observation: in our original assessment, when Grace mimics Justin and buys the new treadmill to catch-up with him both families are now $5,000 poorer. In order to pay back this new debt (or earn back the spending power), the two families need to spend more time at work. Time that they could have spent on experiences that don’t cost money, such as family, friends, community, i.e. things that have been shown to successfully and permanently increase the happiness set-point.

The economic utility formula ignores TIME – the only truly binding limit that Grace, Oliver, you and I have. It ignores time that we could use on activities not involving any exchange of money, but positively and permanently altering our long-term happiness, focusing instead on consumption that is detrimental to our wellbeing, as it creates new time commitments.

Since GDP is a reflection of the consumption-centric economy, higher GDP growth rates not only do not reflect improved welfare, they may actually have negative relationship with welfare (before the whole Economics profession comes down with vengeance on me with data from World Happiness Report and its strong correlation with GDP growth rates, please bear with me until the essay #6 on happiness).

So what is the alternative then, if GDP is not a good measure for our wellbeing? Can we look at the time instead?

Welcome to the real world

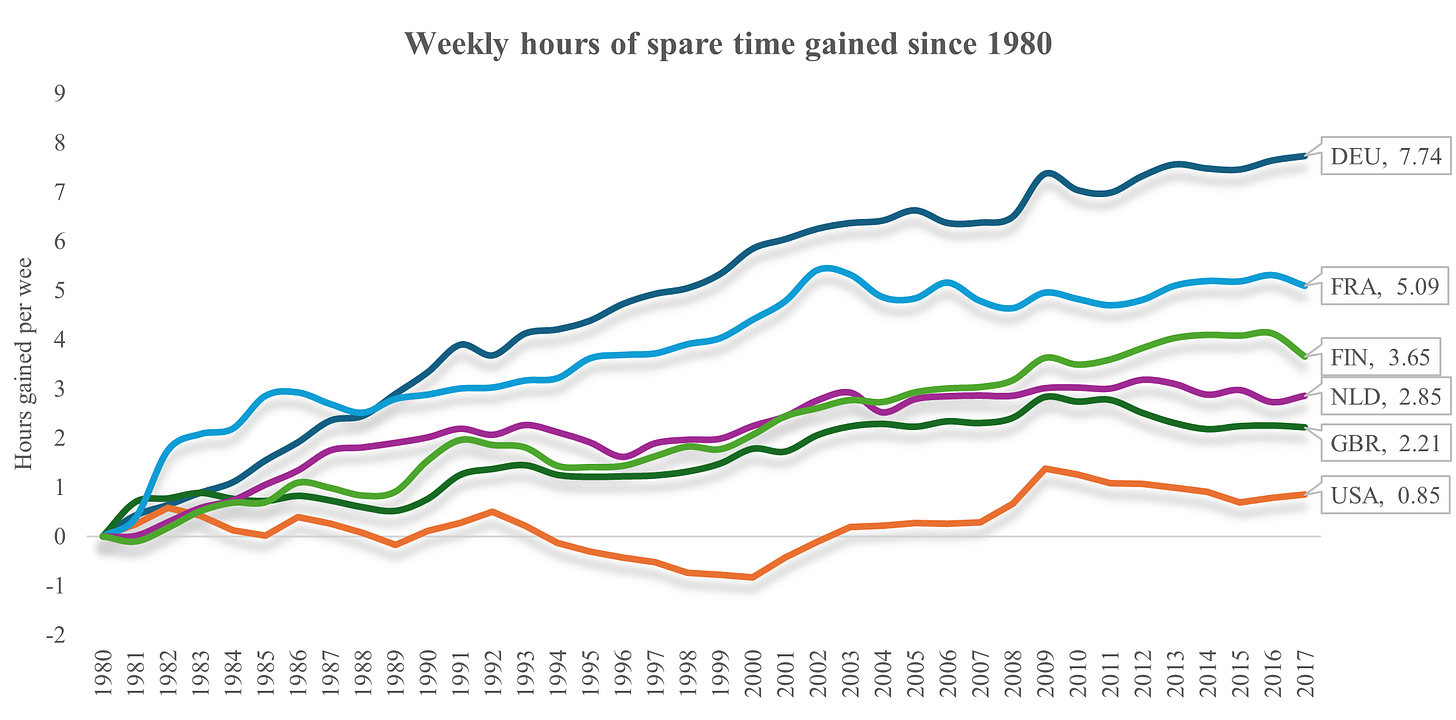

If free time is a key incredient for happiness, how much leisure time do we have in absolute terms and compared to the history? How well do the countries perform in this sense?

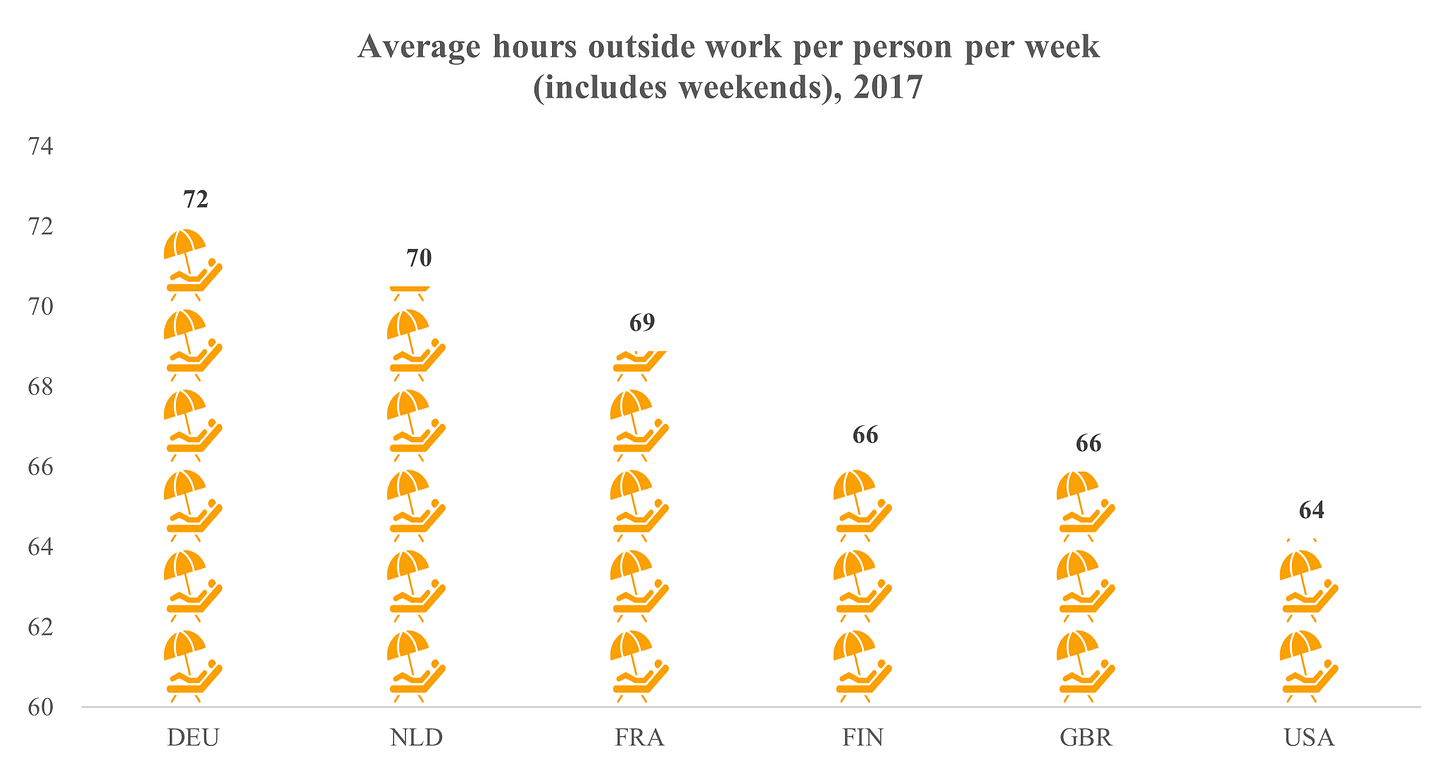

Fortunately, that data is available at Our World in Data. Unsurprisingly, individuals in Germany, Netherlands and France have 12%, 10% and 7% more time outside work per week than in the USA. Inclusion of Finland in the list is not arbitrary. Finland is consistently at the top of happiness surveys, which on the surface appears to contradict our data of limited leisure time, or possibly raise a question about the usefulness of happiness.

An even more curious conclusion is drawn from the historic analysis of improvement in spare time. What has been the progress (economic growth) if we measure what counts?

Despite considerable improvement in the way we produce things over the years (productivity gains), the USA has shown very limited real economic improvement measured in time – less than an hour! In contrast, Germany, France and Finland have added 8, 5 and 3.6 hours of leisure time per week respectively since 1980.

Put it another way: Americans have worked for the sake of working since 1980s.

The reported numbers are average numbers across the economy. But researchers indicate that there is an emerging polarization in the numbers: working hours of highly educated, high-wage, salaried and older-aged men has been increasing.

This was not always the case: most economies (including the US) have delivered considerable improvements in leisure time since 1800s. But the gains have slowed down since 1980s and disappeared altogether in the US. Why?

The hamster wheel

Estimates of working hours in hunter-gatherer societies are around 20 hours a week. Transition to farming increased this number, but created useful seasonal breaks.

The first strong wave of increase in working hours happened in the beginning of the age of industrialization, as people moved from seasonal farm work to hourly work in the factories. At the peak in the 19th century, typical work week in most industrialized economies was nearly 70 hours! This was not by choice, but as an outcome of imposed contracts that maximize profitability, with physical health being the only limit to further increases.

Reduction of working hours until 1980s was achieved by collective bargaining power (trade unions) and regulation (government), not by the market forces. But since 1980s the progress was dealt a triple blow:

trade unions were intentionally and substantially weakened in the US and the UK,

introduction of magnetic stripe on credit cards in 1970s made their universal acceptance a possibility by the early 1980s

planned obsolescence became widely adopted by companies in 1960s-70s after the success of bringing the holding period of a new car from 5 to 2 years by General Motors.

The combination of these factors (and a few others) brought us to a point where Grace, her colleague, you and I are forced into a cycle of consumption to the detriment of our wellbeing. All the while, our economic performance indicators have taken the role of college game cheerleaders: we still measure our policy successes and failures by lauding employment, consumption expenditure and income that merely reflect the speed at which the intentionally constructed hamster wheel spins.

Any suggested shift in policy is examined firmly within the confines of consumption metrics (GDP growth rates) that have nothing to do with appropriate goals for the society. The alarmist report issued by Mario Draghi specifically cites GDP per hour and per person employed as an evidence that Europe is doing worse than the US economically. The conclusions of this report have already been partly accepted by the European Commission as a work plan for the next 5 years.

It appears that our governments and policy makers are caught up in their own hamster wheel of keeping up with the Joneses. At this pace, we are very likely to end up like the Joneses:

-WH