Question 1: Is our system as good as we thought at allocating resources?

The case of futile labour, five hundred watches and children that go hungry.

Tourbillon: the Engineering Marvel

Breguet defeated gravity in 1801. A little more than a hundred years before Wright brothers took to the sky, one of the greatest horologists of the time, Abraham-Louis Breguet, received a patent for his design of a tourbillon – a device to cancel the effects of gravity on the precision of a mechanical watch. Till today the same precision mechanism is highly prised in high-end mechanical watches. This same device also serves as an interesting illustration for an insane resource allocation in our economy.

A mechanical watch keeps time using a balance wheel similar to a pendulum of a clock. The wheel rotates back and forth, and at each extreme moves the gear train forward by one step, making the familiar tick-tock sound. Precise time keeping is a challenge though. If one side of the balance wheel is higher than the other, the movement will not be uniform – gravity will impact the result. In a stroke of engineering genius, Breguet placed the whole mechanism of the wheel in a rotating “whirlpool”, which cancelled most of the effects of the gravity.

Tourbillon was and remains an extremely complex piece of mechanical engineering. In the nineteenth century it cut the daily measurement error of pocket watches from 10-20 seconds to 5-10 seconds! Its production is no small feat, with over 50 tiny pieces and days if not months of fine tuning to make sure that the positive effects outweigh the potential errors introduced by the new rotational movement.

Tourbillon: the Economic Puzzle

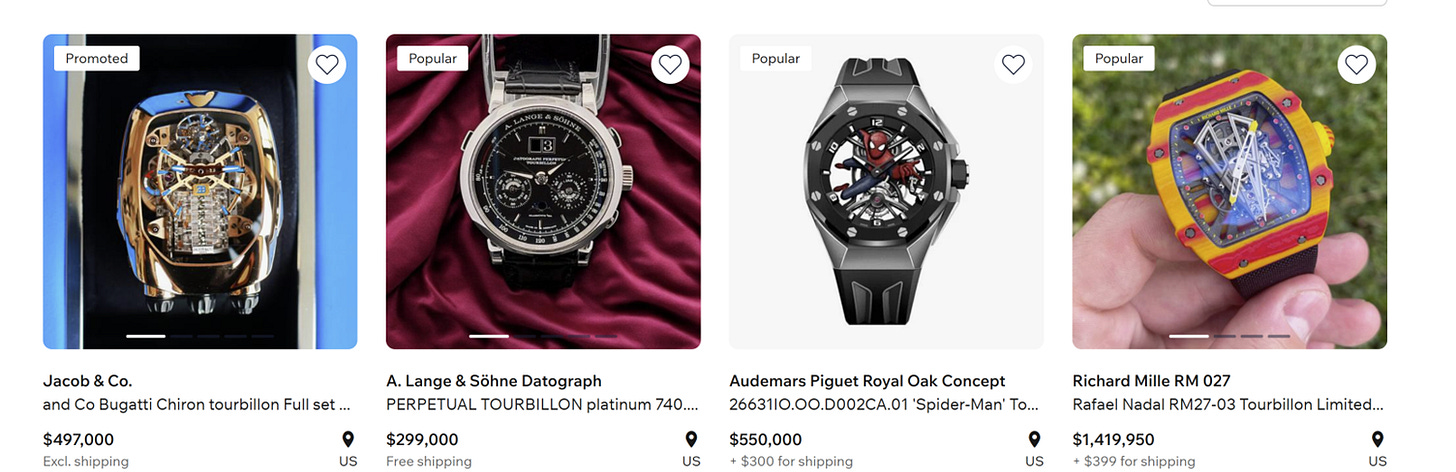

Fascinating device as it is, tourbillon’s significance as an economic puzzle is even more noteworthy. A cursory browsing of today’s online stores of haute horlogerie reveals a good representation of modern tourbillon watches. Since this is a special feature that takes many man hours to get right, it is expected that these watches command a premium.

Except of course, and here is the snag, tourbillon’s relevance as a time keeping technology disappeared entirely the moment the first noble gentleman realised that keeping a watch on the wrist is much more convenient than reaching out for the waist pocket. That’s right, since wrist watches are regularly positioned horizontally, tourbillons have absolutely no measurable effect on the precision of a wrist mechanical watch!

All of this, of course, in turn became completely irrelevant after Seiko gifted the world its first quartz watch in 1969. The best quartz watches today achieve precision of +/- 5 seconds a year, while the most exceptional mechanical watches can show a minimum deviation of 1 second a day in controlled conditions, i.e. 70 times worse than quartz! That’s right: your average $50 battery-operated watch is more precise than a $100,000 mechanical masterpiece!

Now for the big question:

why would consumers pay for artisans in Switzerland, Germany or Japan – three of the most expensive countries in the world to spend an average of 834 hours to hand make an inherently outdated piece of equipment with a component that is entirely devoid of any meaning for over a hundred years?

Exercise in futility?

Prestige and signalling is certainly one explanation: wearing such a device shows the world that one belongs to an exclusive tribe and the value of the piece can signal one’s “plumage”. But some individuals with very evident plumage and in no need of signalling it (see below) still prefer to wear these watches. Art is another explanation, but there are thousands if not millions of aesthetically pleasing works of art that people do not wear and do not buy.

If you engage the enthusiasts in a conversation, sooner or later you will hear phrases like “hand-made”, “craftsmanship”, “intricacy”. A connoisseur of tailor made cloths, bags or custom classic car coaches will tell you that the tiny imperfections found in stitching, soldering or riveting are the reason for the price – the evidence that the piece was hand-made.

The true value lies on their wrist in the form of evidence of 834 average hours of futile, meaningless and back bending work producing a device which could be replaced with a glance at any screen in the vicinity. It is the membership card of the “owners’ club”. Not the owners of watches, but the owners and rulers of other people’s meaningless work. The essence of this attraction is our long-standing fetish of labour – an obsession with toil as a measure of value. The problem is, as we get more and more productive at making things, the number of hours spent on making things become disconnected with the real value added to us.

Business Insider has a YouTube series “Why so expensive” – a collection of videos covering similar items: from lotus silk to Japanese knives, real wasabi and Olympic curling stones. All of the items covered in the series have two things in common: 1) they are produced by hand usually in an extremely difficult environments and involving heavy back-bending work and 2) they have extremely cheap, efficient and mostly superior alternatives. The world of haute horlogerie is not the only ticket to the owners’ club of futile labour.

Back to resource allocation: isn’t there a better way?

The question this raises is whether our common belief that markets allocate resources efficiently and where they are needed is valid, or is still valid? Surely, if the society spends significant resources on things that have no useful meaning, it is sensible to ask whether some alternative uses of these resources are more exigent? The question here is not whether one is justified in wanting to have a piece of art or an artisan object. Rather, whether the social system has the correct priorities: are there needs that most people would consider more important?

Take for instance the number of children classified as “at very low food security” in the United States – the largest economy in the world with the most powerful military in the history of human kind. According to the US Department of Agriculture, there were 841,000 such children – meaning they regularly went hungry. We can’t blame them for being lazy and not pulling their own weight, even if some may make such an argument with respect to their parents. Could we make a dispassionate argument that no matter what system, on the whole, it would make sense to feed these children first, before placing a tourbillon in a mechanical watch?

According to a study carried out by SJX, the very rarefied top of haute horlogerie consists of about 15 brands producing no more than 500 watches a year. This is not the Rolex or Omega group. Wearers of these watches look at Rolex like a Michelin star restaurant patron at a McDonald’s Drive-in sign.

According to the same source, it takes a maximum of 834 hours per watch built in this group (vs. 2-3 hours for a Rolex) and these watches retail at an average of $100,000. Assuming that providing a single child in the US with a basic nutrition would cost $500 a month, a quick math suggests that if 500 gentlemen (almost exclusively) decided to collectively use less menial work and switch to Rolexes or perhaps satisfying their chronometric curiosity by glancing at the screen of one of their devices, 8333 children would be fed. Which is not bad, but you could make an argument that the impact of this resource misallocation is minimal, at only 1% improvement of a chronic problem.

Switching from money to hours

But the real problem is bigger. An assumption here made is that our enthusiasts of mechanical time measurement switch to Rolexes and “pay” for children’s food. Strictly speaking, this does not change the resource allocation, since the watch makers would still make the 500 brilliantly flawed time pieces that would be sold to another set of time lords of excess.

The way to re-allocate the resources would be to switch the watch-making hours to making food, i.e. going from the currency world to the time world (hours spent) – no pun intended. Five hundred watches on average requiring 834 hours of work each means 417,000 hours of work a year.

Amusing as it would be to see a bunch of Swiss watch makers transported to a farm in rural Iowa to grow food, that is not the point of this exercise. The market allocation of resources has “spent” the 417,000 working hours on building devices that serve no real purpose. The question is, what would be the impact of an alternative allocation?

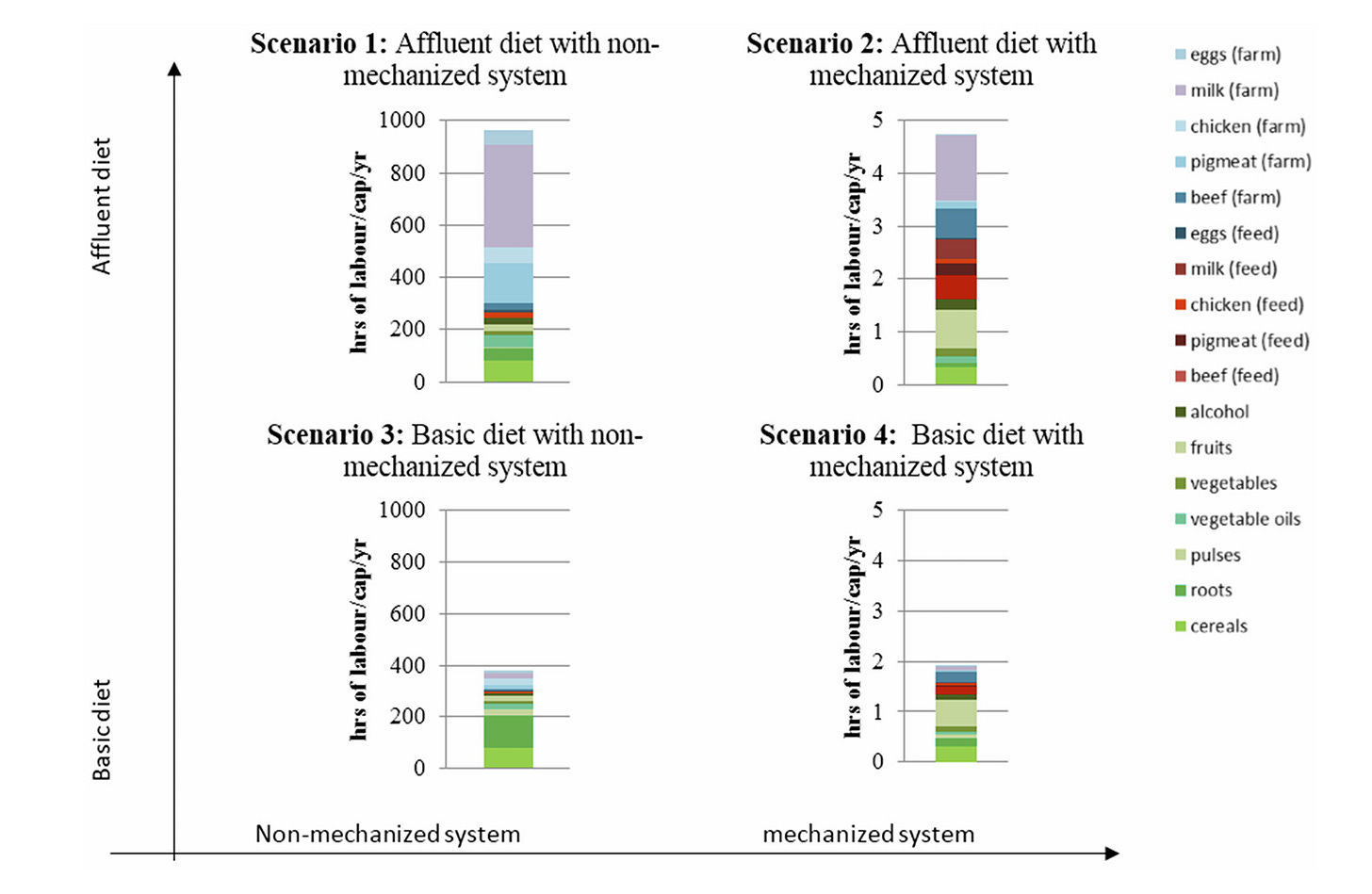

We need to understand how many hours of labour are needed to feed one person for one year. Luckily, an article published in the Resources journal by a team of nutrition experts: María José Ibarrola-Rivas, Thomas Kastner and Sanderine Nonhebel answer exactly this question.

In a mechanised system of food production, it takes only about 1.8-1.9 hours of work per year to feed a single grown adult. Assuming a child requires a little less nutrition, a ballpark number could be 1.5 hours per year. If by some magical and amusing circumstance the Swiss watch makers spent their collective 417,000 hours on food production, they would feed 278,000 children, or more than a third of all children in the US going hungry! As a reminder, we are not talking about the whole world mechanical watch industry, not the higher end of it, but a tiny proportion of the highest customised end of the high end that makes 500 watches annually.

Where does this difference come from? In monetary terms, the switch would make an impact on 8333 lives, while in real hourly terms the impact would be 33 times higher – 278,000 lives!

The difference is at the heart of the biggest issue our society faces: the low productivity of the Swiss watch makers is there by design!

The benefactors of the ancient art of time keeping are not willing to pay for quality equipment produced efficiently. They want inferior products produced inefficiently for the sake of claiming ownership to the exaggerated number of labour hours.

If the reader still doubts this premise, a good exercise would be to imagine the best watch in mind worth USD 100,000 that was made in an entirely automated fashion on an assembly line, without manual labour. Does it still feel expensive?

The system has pushed work to lower productive areas and industries because it found no real need to feed the hungry children. This is not a bug but a feature in our system: since 1990s in the USA every 20 years 15% of all hours worked shift to the equivalent of making mechanical watches – futile labour meant to meet very non-essential requirements.

Let’s not be naïve. Of course, a larger part of the cost of food in the US is processing, transportation, distribution and food waste, so just by wasting less food, or shrinking the margins of the layers of beneficiaries in the supply chain by 0.01% all of this problem would have disappeared entirely. The demonstration in this case is just to highlight the scales of resource allocation inefficiencies.

Although feeding the malnourished children is an example, another allocation outcome is more thought provoking. What would happen to the society as a whole if instead of moving the Swiss watch makers to the rural Iowa, we left them alone where they are, paid the same wages but did not require any work from them? All their daily needs and requirements would be met as they are now. The only missing part would be the complex time pieces. A fair question to ask is: isn’t the society steeling the time of these individuals? How much time is “stolen” in similar industries?

What about the people who will “lose out” from reallocation?

So far the argument for reallocating resources was made entirely from the viewpoint of the recipients of reallocation – the children. But what about the effect on the society at large and the horological heroes in particular: after all, their legitimate need for a specific product can no longer be met. Is there a conceivable negative or as the case may be – a positive effect in this lost consumption?

Paradoxically, making these 500 watches a year disappear in a smoke of mental exercise might actually make the very people who buy them happier. At least to an extent. But a small detour is required to elaborate on what “happiness” means in this context.

The term “happiness” was censured out of Economics texts since the early twentieth century, then reintroduced in the last two decades directly borrowing from a rich idle slave owner from Greece – Aristotle (more on this in another post). His thinking on the subject can be summarized by one word: work. Of course work in his understanding included only reading and writing philosophy texts, while doing useful things like baking bread and making garments was relegated to slaves, who in his opinion were incapable of experiencing happiness (a slight and very ironic misunderstanding of ancient texts by Calvinists, I fear).

The pleasure of owning and enjoying things had nothing to do with happiness in Aristotle’s view. Following this thinking, luxury watch owners could become happier by earning less money and spending the saved time on the study of philosophy. This argument ought to be tested in the galleries of Harrods of London: printed full works of Aristotle instead of the $700 Tom Ford leather belt will make you much happier! Utter nonsense.

But when it comes to the pleasure of any experience, including owning and enjoying things, another Greek philosopher’s views are more relevant – those of Epicurus. These views are nuanced though. Buying an expensive watch is pleasurable and as such, makes one happy. On the other hand, in the words of the philosopher himself (translated from ancient Greek with a huge risk of misinterpretation): “wherever a desire requires intense effort to fulfil, such pleasure is due to idle imagination, and it is not owing to their own nature that they fail to be dispelled, but owing to the empty imaginings of the man.”

The point Epicurus is making, is that having an exclusive watch could be pleasurable, except when there is too much effort involved in getting it or too much fear of not being able to buy it in the future. Although Epicurus wholeheartedly accepts the benefits of pleasure from using luxury items, he warns about the danger of pursuing luxury consumption as a way of achieving a certain status (“safety from other men”). Such a status, in his opinion, is better achieved by having a group of reliable friends. So even the most hedonistic of the ancient philosophers would concede that skipping on a $100,000 watch should not reduce one’s happiness.

Ancient history. What about the modern days? Surely things may have changed since the 4th century BC? Not that much. In a study by T. Kashdan and W. Breen of George Mason University we find that “…people with stronger materialistic values reported more negative emotions and less relatedness, autonomy, gratitude and meaning in life”. Rik Pieters at Tilburg University reports the vicious circles of materialism and loneliness: loneliness pushes towards luxury consumption which in turn reinforces loneliness. As it turns out (surprise, surprise) wearing and exhibiting luxury items makes people measurably less likeable – not exactly a great way to start a friendship.

And now for the question

The balance of evidence then from the ancient philosophers to the modern day sociological studies is that the very people who would miss out on buying the luxury watches would be better off not having them!

So here is the big question:

How can we collectively insist that the current economic system is good at allocating resources, if we have such a glaring example of an insane outcome in which instead of feeding 278,000 children, we make 500 pieces of ornamental nonsense that suck at telling time, making everyone unhappier, including those who buy them and those who make them?

One could argue that we have no business discussing this subject, since we have a free society where everyone is free to work, earn money and spend on any product they desire and that is available for sale. Having the opportunity and the right to buy those watches is the ultimate expression of freedom.

But wait… the same “freedom” argument could be used to justify purchasing illegal drugs, services of a murderer, the Big Ben in London or a complete human being (I take that away, we collectively developed a dislike of the latter only in the past 100 years and not everywhere). So the society draws lines somewhere to define the “rules of the game”. Surely the lines can be redrawn better to avoid outcomes such as this one?

The invisible hand of Adam Smith is at least a little wonky if not detached from a body with a head and eyes. Poor, unfair or inefficient resource allocation is also the smallest of the sins of this economic system, which is directly threatened by this fault. The speed of decline is baked in (the irony that this has been said before at least for a hundred years does not escape the author, but more on this in other posts) and defined by the pace of the technological progress. This failure is brought about and reinforced by other failures that are creating an existential threat to the system: are the resources really scarce? (question 2) and is utility maximization really something we need to do?(question 3).

-WH